The integration of animal and environmental protection into the Constitution has sparked off a political debate on sustainable development.

In recent days, the Institutional Affairs Commission has approved the integration of environmental and animal protection into the Constitution. The proposed constitutional amendments concern, in particular, Articles 9 and 41 of the Constitution: a new paragraph is added to the second paragraph of Article 9, which is among the fundamental principles, for which the Republic “protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation”: it protects the environment, biodiversity and ecosystems, also in the interest of future generations. State law governs the ways and forms of animal protection.

On the other hand, as regards Article 41, which establishes that economic initiative “may not be carried out in conflict with social utility or in such a way as to damage security, freedom and human dignity”, a new paragraph is added: “health and the environment”. Finally, in the third paragraph of Article 41, which states that ‘the law shall determine the programmes and controls appropriate for public and private economic activity to be directed and coordinated for social purposes’, ‘and environmental purposes’ is added.

For the majority in the Senate, this is “a decisive vote that will take our country a big step forward, finally recognising in the fundamental law of our country the protection of animals, the environment, ecosystems and biodiversity, the premise for an epoch-making change that will have to be translated into concrete acts by the State, production and citizens”.

Sustainable Development as defined in the Brundtland Report

The various bills that have been brought before the Institutional Affairs Commission in recent days seem to be flawed because there is no real indication of a constitutional commitment to achieving sustainable development. Probably because, reading them, it seems that the political parties are still unclear about the concept of sustainable development as universally defined in 1987 in the so-called Brundtland Report entitled “Our Common Future”, whose principles of intergenerational and intragenerational equity brought to the attention of the international community led to new developments in the concept of sustainability, which was extended not only to the environmental dimension, but also to the social one. According to the report, ‘sustainable development is development that enables the present generation to meet its own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs’.

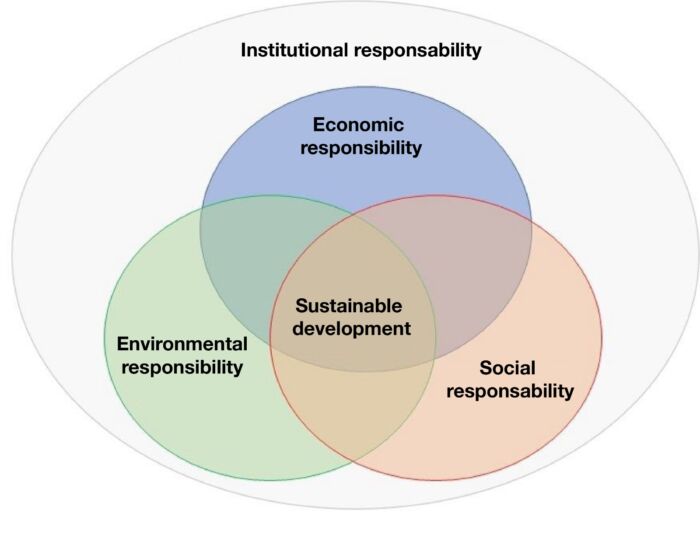

There can be no sustainable development if sustainability does not include, as defined by the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002, the harmonisation of the three dimensions that characterise it: the economic dimension, understood as the capacity to generate income and work in a sustainable manner to sustain the population, the social dimension, understood as the capacity to guarantee conditions of human well-being (security, health, justice, institutions, democracy, participation) equally distributed by class and gender, and the environmental dimension, understood as the protection of the ecosystem, the capacity to maintain the quality and reproducibility of natural resources. “In the long term, economic growth, social cohesion and environmental protection must go hand in hand” (Commission for the Gothenburg European Council, 2001:2). The term “sustainable”, once linked only to its “green” meaning, must now necessarily include economic and social dynamics as well.

The integrated vision of the three dimensions of development must also embrace that of institutional responsibility, which in 2015 led to the birth of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a joint commitment by countries to put the world on a sustainable path.

In order to achieve the sustainable goals set out in the 2030 Agenda, it is to be hoped that political institutions will be willing to include sustainable development in its meaning in the Constitutional Charter, since the SDGs themselves include five P’s for achieving sustainable development: people (to eliminate poverty and ensure dignity), prosperity (understood both as economic ease and as “harmony with nature”), peace (to promote peaceful, equitable and inclusive societies founded on fair and sound systems of justice), partnership (only collaboration between states and businesses makes it possible to achieve the goals) and planet (as an asset to be protected).

The legislative process and the political debate

The process for constitutional revision laws is normally longer than for ordinary laws. The aim seems to be to quickly schedule the reform for a vote in the House. Subsequently, the bill must be adopted by each Chamber with two successive deliberations at intervals of no less than three months, and approved by an absolute majority of the members of each Chamber in the second vote, as provided for in Article 138 of the Italian Constitution.

The hope, however, is that the current proposal will be revised by integrating it with other proposals put forward in 2018 (Bill 240 and Constitutional Bill 938), which may have inspired Prime Minister Mario Draghi, during his reply to the Senate, before the explanations of vote on the confidence in his new executive, by giving his full support to parliament in including the concept of sustainable development in the Italian Constitution.

In particular, the above-mentioned proposals call for the amendment of Articles 2 and 9, which deal with fundamental principles, and Article 41, including the part regulating economic relations, in the following new version:

– Article 2: The Republic recognises and guarantees the inviolable rights of man, both as an individual and in the social groups where his personality takes place, and requires the fulfilment of the imperative duties of political, economic and social solidarity also towards future generations.

– Article 9: The Republic promotes the development of culture and scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation. It recognises and guarantees the protection of the environment as a fundamental right of the individual and an interest of the community. It promotes the conditions for sustainable development.

– Article 41: Private economic initiative is free. It may not be carried out in conflict with social utility or in such a way as to harm the environment, security, freedom or human dignity. The law determines the programmes and controls that are appropriate so that public and private economic activity may be directed and coordinated for social purposes and sustainable development.

The battle to introduce sustainable development into the Constitution in its broadest sense seems set to ignite political debate in the coming months, given the scope of the press release on behalf of the first signatory of Bill 240 in the Chamber of Deputies, Mauro Del Barba, in which he expresses his disappointment at the first yes vote in the Institutional Affairs Committee. According to Del Barba, the alleged inclusion of sustainable development in the Constitution does not actually exist, because “a timid reference ‘also’ to future generations on environmental issues is not enough to affirm, in 2021, that we have understood the epochal significance of what the Brundtland Commission defined with extreme clarity in 1987 and which the whole world is now pursuing in its economic, social and environmental dimensions. We do not need flags to wave, but – he concludes – universally recognised criteria capable of definitively committing Parliament to the pursuit of the well-being of future generations”.

This debate is necessary to ensure that when the Constitutional Charter is amended, this is done in due depth and in a complete and comprehensive manner. There is a bad habit when talking about sustainability or sustainable development: to associate it only with the environmental dimension. If we only include the right to environmental protection in Article 2 of the Constitution, we are not even “halfway through”. Political institutions have a duty to “promote sustainable development”, to be integrated as in the 2018 proposal, in Article 9, but above all to “make the economy,” in particular economic operators (see businesses) “responsible” for not damaging the ecosystem and its biodiversity, and then it must be understood that to achieve Sustainable Development it is necessary to “harmonise” the three dimensions of sustainability: economic, social and environmental.