Background

The effects of climate change on Swiss glaciers caused by global warming, which is in turn caused by high greenhouse gas emissions, primarily carbon dioxide, are increasingly evident. Glaciers have been retreating gradually for the past century, with a loss of volume averaging 2% per year over the past decade. As the glaciers melt, it is inevitable that Switzerland will lose an important water supply. According to SwissInfo’s estimates, Switzerland would only be able to provide its population with drinking water for another 60 years.

Despite the country’s small size, the Swiss Confederation has a very high ecological footprint, due to high levels of consumption, road transport – despite an efficient and extensive public transport network – and high energy consumption for domestic use.

However, agriculture also bears responsibility, and not only for the production of greenhouse gases. The use of chemical pesticides is a further indictment. SwissInfo’s analysis of FAO data shows that Switzerland uses less pesticides than Italy (4.9 kg/ha compared with 5.9 kg/ha in Italy) but more than France (4.5 kg/ha), Germany and Austria (both 3.8 kg/ha), to name but a few of its neighbours.

Initiatives and promoters

By signing the Paris Agreement, the Confederation committed itself to halving greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. To honour this commitment, it decided, after lengthy negotiations in parliament, to ask the Swiss people to vote on three environmentally-oriented referendums: two concerning the preservation of clean drinking water and a ban on the use of pesticides, supported only by the left and part of the centre, and the CO2 Act supported by all political parties except the Centre Democratic Union (a conservative right-wing political party).

The questions

1. Clean drinking water and healthy food – No subsidies for the use of pesticides and the prophylactic use of antibiotics”.

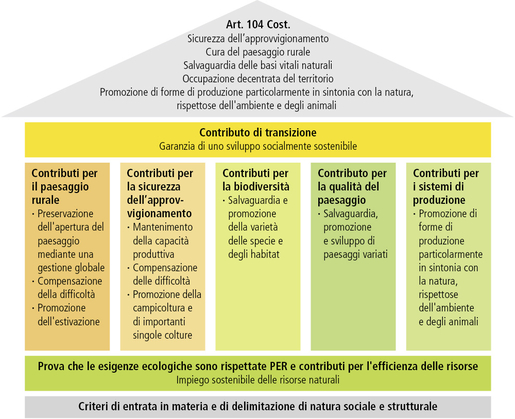

Direct payments account for the largest share of the Swiss government’s agricultural budget. In particular, these subsidies are paid to farms that cultivate the land and are run by entrepreneurs under 65 years of age with specific professional training in agriculture. The maximum amount of CHF 70,000 per standard labour unit (UMOS) is only granted if the farm requires the work of at least 0.20 UMOS and if at least half of the work required for the operation of the farm is carried out by in-house labour. To this must be added the ecological burdens that farmers must comply with, providing evidence of their compliance. Below is a diagram of their distribution drawn up by the Federal Office for Agriculture – FOAG.

Source: Federal Office for Agriculture – FOAG.

The referendum initiative committee considers these charges to be insufficient and therefore calls for direct payments to be made only to farms that do not use pesticides, that do not regularly use antibiotics for prophylactic purposes on their farms and that are able to feed their animals exclusively with fodder from their own production, in order to avoid excessive manure and slurry spillage, to preserve water and also to direct agricultural research, advice and training towards these goals. The initiative would not affect less virtuous farms that do not receive direct payments, and are still not sanctioned in any way.

The Federal Council and Parliament have warned voters that acceptance of the initiative, which they believe has excessive standards, could lead to a decrease in local agricultural production, with the obvious consequence of increasing food imports to support national needs.

According to the initiating committee, the massive use of pesticides, antibiotics and excessive spreading of slurry on fields violates the right to clean drinking water, and a reorientation of subsidies would be desirable to limit environmental damage and health risks.

2. “For a Switzerland without synthetic pesticides”

The initiative would ban the use of synthetic pesticides in Switzerland not only, of course, in agriculture, food production and processing, but also in the maintenance of public green spaces, private gardens and infrastructure (e.g. railway tracks). The import of foodstuffs from abroad containing synthetic pesticides or in the production of which they have been used would also be banned. During the adjustment period of 10 years after acceptance of the initiative, the Federal Council could allow exceptions to counteract a serious threat to agriculture, the population or nature.

The Federal Council and Parliament consider this ban to be disproportionate and have spoken out against it, advising voters to do the same. In their view, the domestic and foreign supply of food would be severely restricted, and the ban would violate international trade agreements.

3. Federal Act on the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (CO2 Act)

In order to further reduce carbon dioxide emissions, the law provides for a combination of financial incentives, investments, new technologies, as well as increased costs for those who generate the most CO2.

For example, the renovation of buildings, the construction of recharging stations for electric vehicles and the introduction of other vehicles that use less petrol and less diesel would be encouraged. Importers of these types of fuel would, however, incur additional costs to finance investments in reducing their environmental impact, and to compensate for this, they could increase the price at the pump. The price of oil, heating gas and flight tickets would also be increased.

Given that rising temperatures lead to melting glaciers, heatwaves, droughts and landslides, both the Federal Council and Parliament welcome this initiative as an effective way of combating climate change. Additional orders for Swiss SMEs and job creation in the field of new technologies would be just some of the positive effects of the measures.

The “Economic Committee NO to the CO2 Act”, which is led by the motoring and mineral oil industry associations, is strongly opposed to the initiative. It considers the law to be costly, to have little impact on the global climate – Switzerland would only produce one per thousand of global CO2 emissions – and, above all, to be unfair, since the measures would hit the lower and middle income groups hardest.

The results of the consultations

On 13th June, around 60% of Swiss voters rejected all three environmental questions. The real surprise was the NO vote on the CO2 Act which, despite the approval of the cantons of Geneva, Vaud, Neuchâtel, Basel City and Zurich, received 51.7% of the total vote. Basel-Stadt, in particular, was the only canton whose majority also voted in favour of the questions “Clean drinking water and healthy food” and “For a pesticide-free Switzerland”, while Geneva and Zurich recorded a balanced but negative result on these two issues.

Swiss environmental policy: Quo vadis?

Sommaruga, the environment minister, and the Green Party are disappointed with the outcome of the polls, saying that it will have a negative impact on the country’s future and on the achievement of the EU’s shared goal of climate neutrality by 2050.

However, it is legitimate to wonder whether a different formulation of the questions, less demanding on some aspects and more incentive-based on others (e.g. a reduction in the cost of the exorbitant General Abonnement for Swiss public transport in order to encourage its use), would have returned a different result and contributed to even a small advance towards the ambitious goal.

The negative result comes on top of that of another popular initiative rejected on 29 November last year, which concerned the civil liability of multinationals with headquarters in Switzerland for the violation of human rights or international environmental standards by their foreign subsidiaries. Had there been approval, individuals or organisations would have been able to take legal action against an alleged violation in Switzerland, where the company’s headquarters are located and where more punitive laws presumably apply than in other countries. Another missed opportunity.