The war is largely driven by the eruption of long-standing antagonisms between neighbouring, often loosely mixed clans, sects and actual peoples. In Iraq and Syria, it is a clash between Sunnis, Shiites, Kurds, Turkmen and others; in Nigeria, between Muslims, Christians and various tribal groups; in South Sudan, between the Dinka and Nuer; in the East and South China Sea, between Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Filipinos and others; in Ukraine, between Ukrainian loyalists and Russian speakers aligned with Moscow. It would be easy to attribute all this to age-old hatreds, as many analysts suggest; but while such hostilities certainly help to steer these conflicts, they are also fuelled by a more modern impulse: the desire to control valuable oil and gas resources. Make no mistake about it, these are 21st century wars for Energy.

It should come as no surprise that Energy plays a significant role in these conflicts. Oil and gas are, after all, the most important and valuable commodities in the world and constitute a major source of income for the governments and companies that control their production and distribution. Indeed, the governments of Iraq, Nigeria, South Sudan, Syria and Russia derive much of their revenues from oil sales, while large energy companies – many of them state-owned – wield immense power in these and other countries involved. Despite the apparent veneer of historical enmities, many of these conflicts, therefore, are actually struggles for control of the main source of national income.

We also live in an energy-centric world where control of fossil resources (and their carriers) translates into geopolitical clout for some states and economic vulnerability for others. Because so many countries depend on energy imports, nations with surpluses to export – including Iraq, Nigeria, South Sudan and Russia – often exert an influence disproportionate to their real political clout on the world stage.

The struggle for energy resources has been an obvious factor in several recent conflicts, including the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988, the Gulf War of 1990-1991, the Sudanese civil war of 1983-2005, and not least the war between Russia and Ukraine that began on 23rd February. At first glance, the fossil fuel factor in the most recent outbreaks of tension and war may seem less obvious. But a closer look reveals that each of these conflicts is, in fact, a war for Energy.

All wars are fought for money.

Socrates in ‘War and Peace’

The Russia-Ukraine War

The current crisis in Ukraine began in November 2013, when President Viktor Yanukovich repudiated an agreement to tighten economic and political ties with the European Union (EU), opting instead for closer ties with Russia. This act sparked fierce anti-government protests in Kiev and eventually led to Yanukovych himself fleeing the capital. With Moscow’s main ally put out of action and pro-EU forces having taken control of the capital, Russian President Vladimir Putin moved to take control of Crimea and to foment separatist pressures in eastern Ukraine. For both sides, the resulting struggle was about political legitimacy and national identity – but as in other recent conflicts, the Energy issue was also in the background.

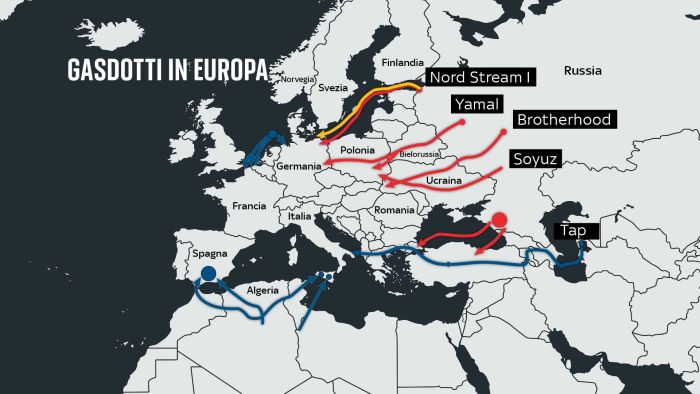

Ukraine is not a major energy producer per se. It remains, however, an important transit route for the supply of Russian natural gas to Europe.

The news of the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian armed forces, which began in the night of Wednesday 23rd to Thursday 24th February, has inevitably gone round the world and the critical war situation taking place on European soil is constantly in the spotlight. There are currently no plans for direct intervention by NATO in support of Ukraine, as it is not a member of the organisation. However, a package of sanctions against Russia has been approved which, for the time being, does not involve the gas energy sector.

Are we at risk of an energy crisis?

Could Europe without gas from Russia succeed? The main concern for Europe and, in particular, for Italy is mainly the supply of gas, This is why at the extraordinary summit of EU Heads of State and Government several countries were reluctant to include gas in the debate. The reason is the strong dependence of different European countries on gas from Russia, which has the largest (proven) reserves in the world.

Overall, it can be said that the current supply and storage situation puts Europe in an advantageous position, both to face 2022 without Nord Stream 2 and to prepare for the coming winter; however, 2023 will start to show problems due to the progressive decrease in domestic production, combined with the lower availability of LNG supply for Europe.

The energy crisis and its consequences for Italy

Europe can meet the demand for gas for now, but the long-term prospects are uncertain. Let’s look at the situation in Italy: about 46% of the gas used in our country comes from Russia and is used to produce about 60% of our electricity.

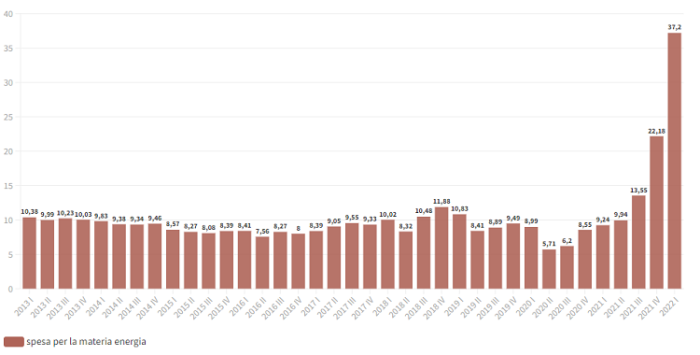

The consequences of this dependence have already been felt loud and clear, with the soaring costs that have affected the latest bills and the closure of several businesses precisely because of these increases; costs that, with the worsening of the Russian-Ukrainian situation, are marking further rises, with the price of methane on the Amsterdam market, a benchmark for continental Europe, reaching 125 euros per MWh.

As stated by President Draghi during his briefing to the Chamber of Deputies on 25th February, the sanctions approved, those that may be approved in the future and the situation already experienced due to price increases, inevitably lead to the need to make considerations regarding the impact on the national economy and the agreements reached so far.

The imprudence of not having diversified energy sources and suppliers more in recent decades is being felt, and this imprudence must be remedied in a timely manner to avoid the risk of future crises, given the current phase of transition, not only energy but also geopolitical transition.

The need to accelerate the transition to renewables is once again evident and put to the test by the war events of recent days. In parallel, given the inevitability of gas as a transition fuel in the coming years, all opportunities to further diversify the mix of supply countries should be explored, including the strengthening of the Southern Corridor, as well as increasing national production.

Might it be time to start thinking about the possibility of using green hydrogen alongside renewables in the future?

Download the SmartGreen Post Magazine FOR FREE HERE