Climate change, in addition to causing serious problems to natural ecosystems, infrastructure, housing, businesses and livelihoods, is having (direct and indirect) impacts on people’s physical and mental health. Susan Clayton, of the Department of Psychology at the College of Wooster in Ohio, explains in her study ‘Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change’ how the most obvious effects of climate change are certainly those on physical health, which will be increasingly threatened by heat, the increased spread of water-borne and vector-borne diseases, and malnutrition, in addition to the impacts caused by natural disasters, forced migration and conflict. The effects on mental health, while less obvious, are not to be overlooked, however; indeed, it has been observed that the physical consequences of climate disasters are often much less than the psychological ones (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2010).

In recent decades, there has been an increase in research testifying to the impact of natural disasters on mental health, showing increased levels of PTSD (‘Post Traumatic Stress Disorder’), depression, anxiety, substance abuse and even domestic violence problems following the experience of storms, and increased rates of suicide and hospitalisation for mental illness related to heatwaves. In addition, the study says, several studies are being conducted that would prove that poor air quality can also have impacts (both short-term and long-term) on mental health. Indeed, climate change is accompanied by increasing levels of air pollution as the combustion of fossil fuels tends to produce pollutants such as particulate matter, ozone and carbon that are trapped in warmer air. Several studies have found a correlation between the level of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) and cognitive impairment in the elderly or behavioural problems in children.

The sense of helplessness, distress, fear and anxiety caused by climate change and natural disasters in general is increasingly widespread, especially among young people. More than ten years ago, the British scientific journal The Lancet and the Institute for Global Health at University College London called climate change ‘the greatest threat to global health, and to mental health in particular, in the 21st century’. The American Psychological Association (APA), in a 2017 study, defined eco-anxiety as ‘the chronic fear of environmental ruin’, although there are multiple definitions in the scientific literature. The term ‘eco-anxiety’ was coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, who describes it as ‘the generalised feeling that the ecological foundations of existence are about to collapse’. This disorder, however, has not yet been included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) and is therefore not recognised as a medical-psychological condition, but rather as an understandable reaction to the severity of the ecological crisis, although in many cases eco-anxiety is so strong that it still requires psychological support.

Obviously, this condition of discomfort mainly affects those who experience the climate crisis at first hand, such as people who become homeless or are forced to leave their homes due to extreme weather events, or who suffer the effects of rising sea levels, droughts or unpredictable weather conditions. Naturalists, climate scientists and all those who, for personal and/or cultural reasons, care more about environmental issues or feel in some way connected to the natural world, also tend to suffer more from eco-anxiety. However, several studies testify that an increasing number of people are experiencing a feeling of anxiety related to the global environmental crisis even without experiencing its direct or indirect effects. The mere fact of learning about the consequences and effects of climate change through the media or other sources of information, in fact, can have a negative impact on mental health, usually resulting in: stress, alienation, depression, anxiety, feelings of overwhelm, panic attacks, insomnia, obsessive thoughts, suicidal impulses, increased aggression and, in some cases, the possibility of not wanting to have children as it would be unethical because of the future quality of life.

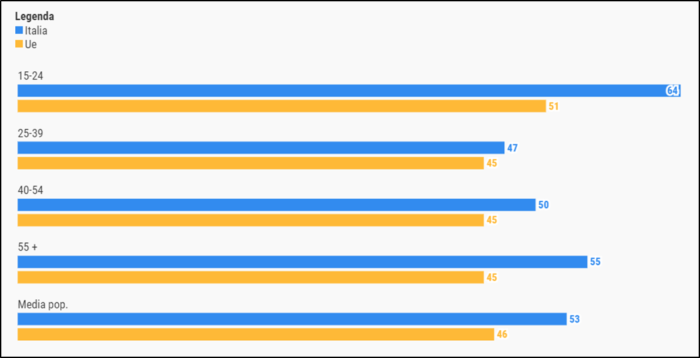

Openpolis has processed data from a 2022 Eurobarometer survey, calculating the percentage of people in each age group who answered “very concerned” to the question: “To what extent are you currently concerned or not concerned about each of the following issues for your life and that of your loved ones? (climate change)”. The data showed that 51% of young Europeans aged 15 to 24 say they are very concerned about climate change, compared to 45% in the other age groups. For Italy, the generation gap is even wider as almost 2 out of 3 young people are very concerned about the climate, compared to an average of 53% in the overall population.

(Published: Tuesday, 17 January 2023)

A Save the Children survey conducted between May and August 2022, involving more than 42,000 children and adolescents in 15 countries (including Italy), showed that 4 out of 5 children say they witness climate change or social inequality, or both. As many as 84% of those who answered the questionnaire also stated that they observe a deterioration in the mental well-being of children and adolescents in relation to climate change and inequality. In Italy, 3 out of 4 young respondents believe that the richest countries are the most responsible and that states should collaborate and act concretely, helping the poorest families and children. In general, the need emerged among respondents to be helped to understand these problems (37%), supported with training (34%) or funding (32%) and to have safe spaces to meet (33%).

Several authors have noted a common feeling of apprehension among young people about the fate of young people in other countries who are already experiencing the direct impact of climate disaster (Burke et al., 2018). For some, this concern relates to their own future, referring to declining biodiversity, increasing pollution and, in the most extreme cases, the end of the world and life on Earth (Huang H., Yore L., 2005). Parallel to feelings of fear, anger, anxiety, pessimism, guilt and despair, however, young people can also harbour feelings of hope with regard to climate change. Two studies have shown that concern and hope are positively correlated (Stevenson K., Peterson N., 2016) and that confidence in the future goes hand in hand with action (Ojala M., 2012a). In fact, while eco-anxiety can result in a feeling of helplessness and paralysis towards the immensity of the ecological problem (Wolf J., Moser S., 2011) and sometimes even lead to its denial (Albrecht et al., 2007), it can also lead to action, mobilisation and, therefore, the desire to change one’s habits to help the planet. This sense of rebellion has emerged especially in recent years, thanks to the demonstrations of the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg who, with her slogan Skolstrejk för klimatet (‘School Climate Strike’), has raised awareness of climate change and sustainable development issues among millions of people worldwide, giving rise to the international student movement Fridays for Future.

Certainly, parents have a crucial role in educating today’s children, who will be tomorrow’s adults, to respect the environment and to adopt virtuous behaviours (such as recycling, reducing consumption and buying sustainable products), which must involve the whole family. Educators and teachers also play a crucial role in educating, guiding, raising awareness and listening to their students’ emotions about climate change, providing them with a suitable and safe space to openly share their experiences and feelings. Of course, a healthy concern for the fate of our Planet can help us not to remain indifferent to the problem and to want to take concrete actions to feel an active part in the change.

Those who think they suffer from eco-anxiety, first of all, must bear in mind that this condition of discomfort and unease can be controlled and managed. Researchers agree that concrete actions such as participating in ecological initiatives, practising small but important daily actions, sharing one’s concerns, getting well informed and being in contact with nature can certainly help. If one realises, however, that the symptoms associated with anxiety about environmental issues become an obsession and end up paralysing one’s daily life, it is essential to talk about it with someone (friends or family members), reduce media exposure during the day, and consult a specialist (psychologist/psychiatrist), as recommended by Giampaolo Perna, full professor at Humanitas University and head of the Centre for Personalised Medicine on Anxiety and Panic Disorders at Humanitas San Pio X.

As a form of malaise that has emerged in recent years, eco-anxiety is still the subject of study and research, but it is important to understand, normalise and accept the emotions associated with the climate and the future of the planet, to raise public awareness of the issue and not to make those who suffer from it feel alone and misunderstood.